Total Internal Reflection

Technology and Art

Code

Contact

Vectors, Normals, and Hyperplanes

Linear Algebra deals with matrices. But that is missing the point, because the more fundamental component of a matrix is what will allow us to build our intuition on this subject. This component is the vector, and in this post, I will introduce vectors, along with common notations of expression.

We will talk about the normal vector, and its relation to a line, a plane, and ultimately, a hyperplane. We will introduce the idea of the dot product (though I’ll not be delving into it only in a later article).

Vectors

It is very instructive to look at a single vector. Remember that our worldview is that a matrix is just a bunch of vectors. We will return to this point later.

The convention for defining vectors you will find in every textbook/paper is as a column of numbers (basically a column vector). We’d write a vector \(v{1}\) as:

\[v_1=\begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ \end{bmatrix}\]Vectors implicitly originate from the origin (in this case, \((0,0)\)). We take

\[v_2=\begin{bmatrix} x_{11} && x_{12} \\ x_{21} && x_{22} \\ \end{bmatrix}\]You can look at \(v{2}\) in two ways:

A set of two column vectors, i.e., \(\begin{bmatrix} x_{11} \\ x_{21} \\ \end{bmatrix}\), \(\begin{bmatrix} x_{12} \\ x_{22} \\ \end{bmatrix}\)

or, a set of two row vectors, i.e., \(\begin{bmatrix} x_{11} && x_{12} \\ \end{bmatrix}\), \(\begin{bmatrix} x_{21} && x_{22} \\ \end{bmatrix}\)

The column vector picture is usually more prevalent. Usually, if a column vector needs to be turned into a row vector (for purposes of multiplication if, say, you are trying to create a symmetric matrix), you’d still consider it as a column vector, and use the transpose operator, written as \(v^T\).

Lines, Planes, and Hyperplanes

Let’s talk a little bit about lines, surfaces, and their higher dimensional variants (hyperplanes) and their normal vectors.

1. Lines

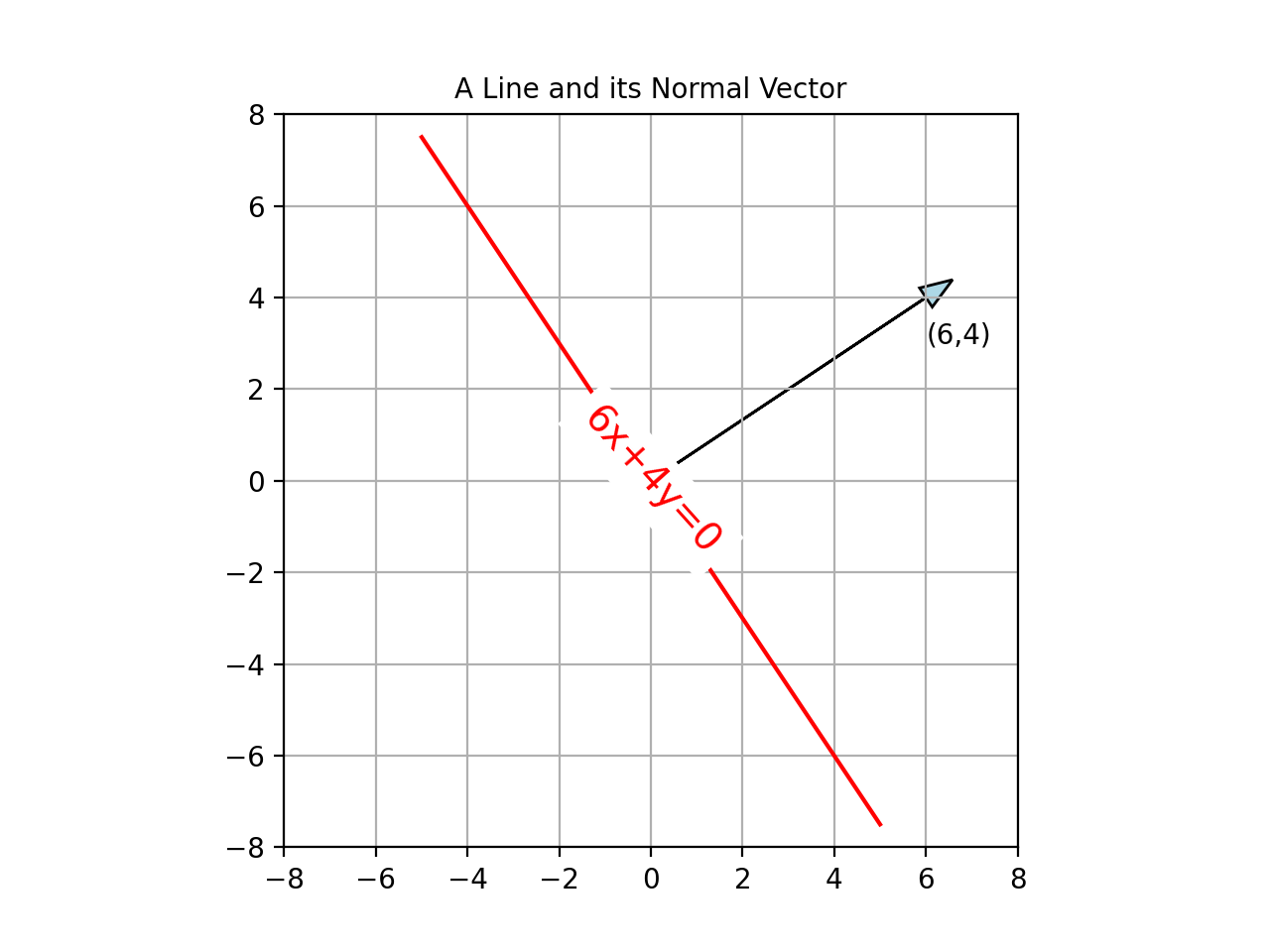

Here’s a line \(6x+4y=0\). I’ve also drawn its normal vector which is \((6,4)\). Now, note the direct correlation between the coefficients of the line equation and the normal vector. In fact, this is a very general rule, and we will see the reason for this right now.

Quick Aside: Why is \((6,4)\) the normal vector? This is because any point on the line \((6x+4y=0)\) forms a vector with the origin, which is perpendicular to the normal vector (which obviously translates to the entire line being perpendicular to the \((6,4)\) vector). This is shown below.

We haven’t talked about the dot product yet (that comes later), but allow me to note a painfully obvious fact, any point on the line \(6x+4y=0\), satisfies that equation. Indeed, you can see this clearly if we take \((2,-3)\) as an example, and write:

\[6.(2)+4.(-3)=0\]Let us interpret this simple calculation in another way. This is like taking two vectors \((6,4)\) and \((2,-3)\) and multiplying their individual components, and summing up the results. \((2,-3)\) is obviously the vector we chose, and \((6,4)\) is another vector, which in this case, is…our normal vector.

This operation of multiplying individual components of vectors, and summing them up, is the dot product operation. It is not obvious that taking the dot product of perpendicular vectors will always result in 0, but we will prove it later, and it is true in the general case.

Indeed, an alternate definition of a line is the set of all vectors which are perpendicular to the normal vector (in this case, \((6,4)\)). This is why a line (and as we will see, a plane, and hyperplanes) can be characterised by a single vector.

Quick Aside: There are alternate ways to express a line (or plane or hyperplane) using vectors which involve the column space interpretation, but I defer that discussion to the Vector Subspaces topic.

The dot product operation is denoted as \(A\cdot B\), and I’ll defer more discussion on the dot product to its specific topic.

2. Planes

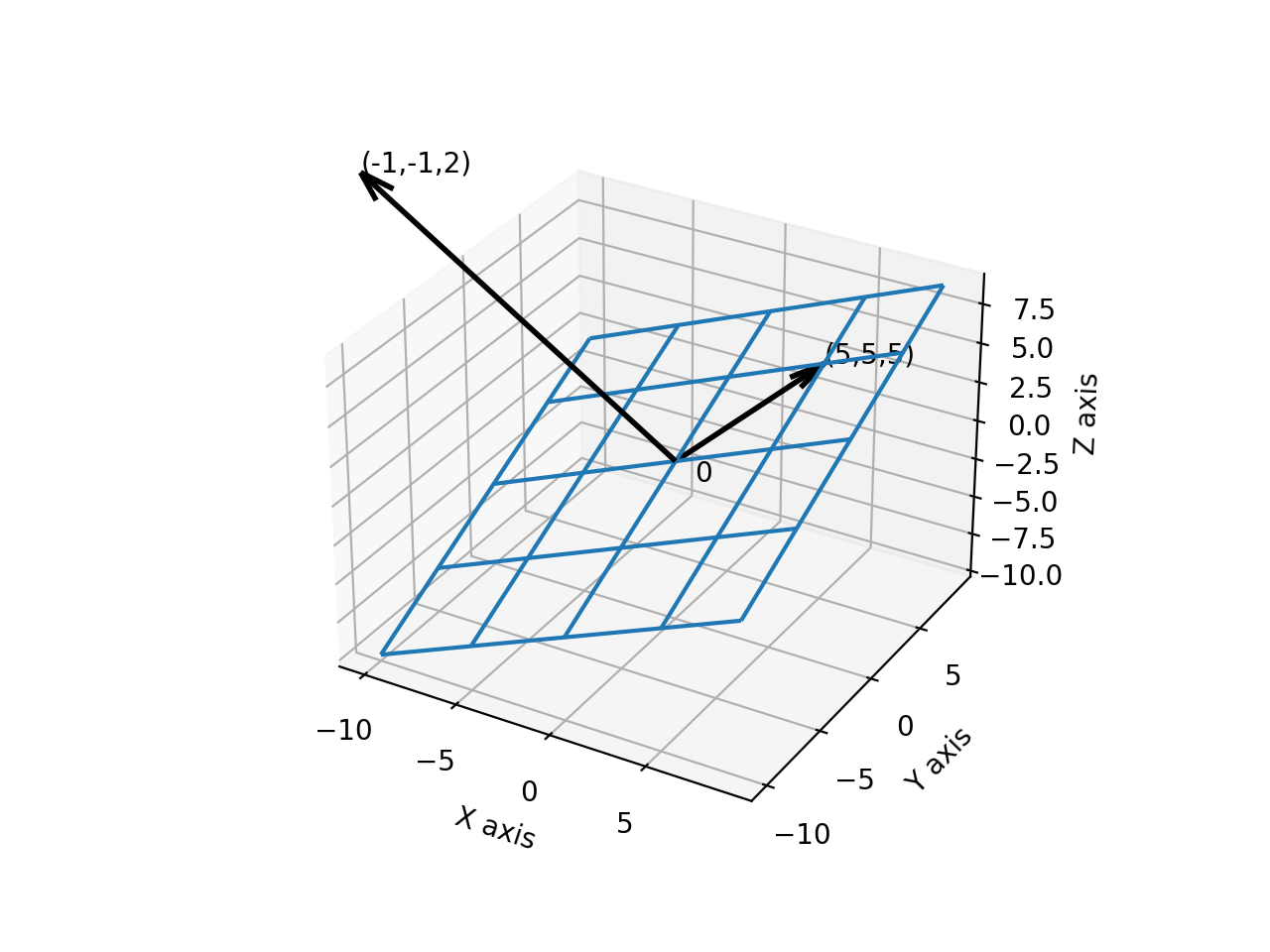

Let’s move up a dimension to 3D. Here we consider a plane of the form:

\[ax+by+cz=0\]To make things a little more concrete, consider the plane:

\[-x-y+2z=0\]and a point on this plane \((5,5,5)\).

Do verify for yourself that this point lies on the plane. Also, as you can see, the coefficients of the plane equation form the normal vector of the plane. The same concept that applied to lines, also applies here.

In other words, satisfying the condition that a point (or vector) lies on a plane (hyperplane) is the same thing as satisfying that the vector is perpendicular to the normal vector of that plane (hyperplane). It is literally the same computation, thanks to how dot product is defined.

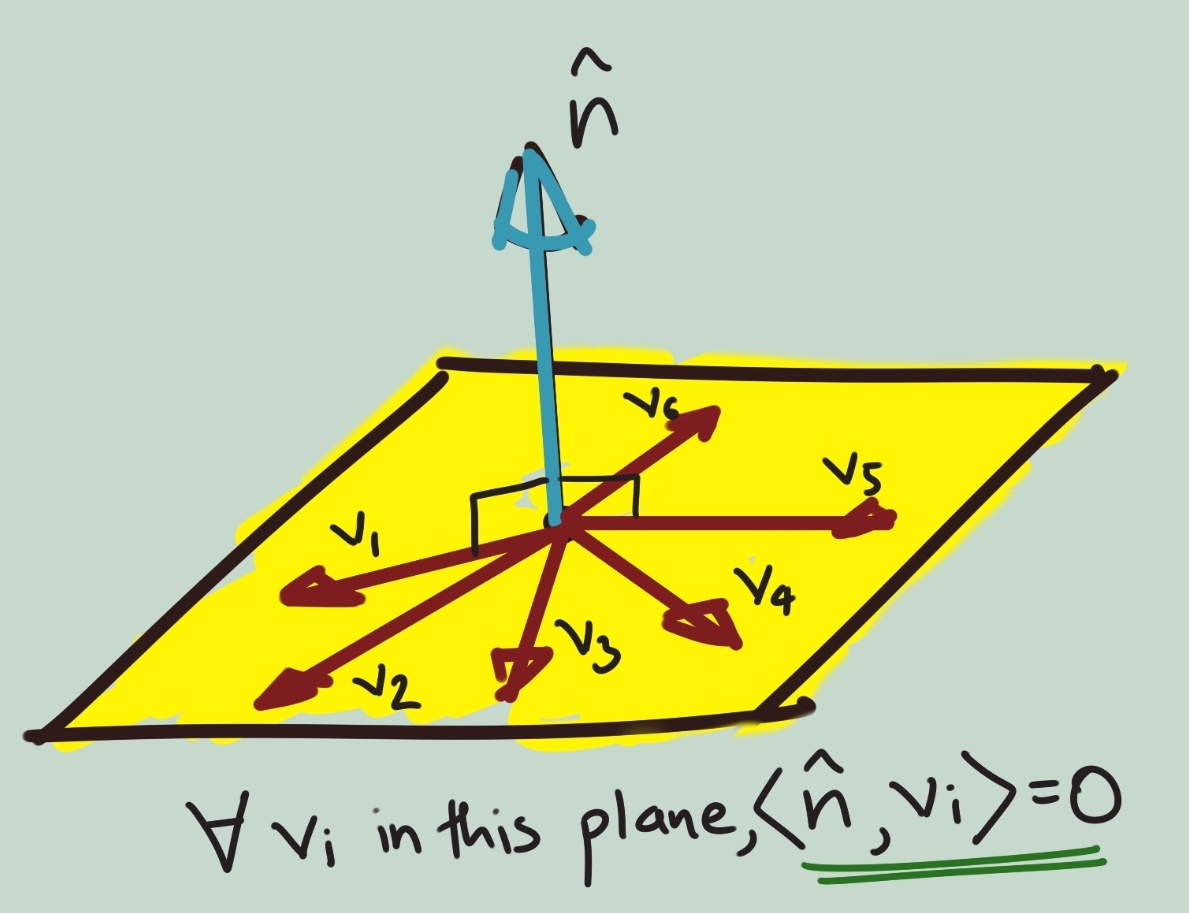

The image below illustrates this idea.

3. Hyperplanes

We can extend the same concept to higher dimensions, except we cannot really sketch it out (at least in a way that would make intuitive sense to us). Incidentally, it’s just easier to refer to everything as a hyperplane when talking in the abstract, since a line is a one-dimensional hyperplane, a plane is a two-dimensional hyperplane, and so on.

Note: I’d like to make the definition of a hyperplane explicit with respect to its dimensionality. A hyperplane in a vector space with dimensionality \({\mathbb{R}}^N\) is always of dimensionality \(N-1\), i.e., one dimension lesser than the ambient space it inhabits.

This guarantees a unique normal vector for that hyperplane, because by the Rank Nullity Theorem, the null space (where the normal vector resides) will have only one basis. As a counterexample, a 2D plane in \({\mathbb{R}}^4\) would have two linearly independent normal vectors, and thus does not qualify as a hyperplane in 4D space (but does qualify as one in 3D space).

What this implies is that any hyperplane defined as:

\[w_1x_1+w_2x_2+w_3x_3+...+w_nx_n=0\]has its normal vector as: \(v=\begin{bmatrix} w_1 \\ w_2 \\ ... \\ w_n \\ \end{bmatrix}\)

Incidentally, the above form is the most common form of expressing a hyperplane, i.e., by referencing its normal vector.

Relevance to Machine Learning

In addition to vectors (and by extension, matrices) being used to frame almost every Machine Learning/Statistics problem, these are some examples of how they are used:

- Many Machine Learning problems related to prediction boil down to determining a hyperplane that best captures the trend of the data, subject to certain assumptions (eg: Linear Models/Generalised Linear Models).

- Many Machine Learning problems related to classification, boil down to finding the optimal dividing hyperplane between two different classes of data (eg: Support Vector Machines).

- Relationships between vectors give us important information about the space that they define (more on this in Vector Subspaces). This in turn can help us infer information certain important properties of a matrix (invertibility, eigenvectors, etc.). This can directly tell us whether certain Machine Learning processes can be applied or not.

tags: Machine Learning - Linear Algebra - Theory