Total Internal Reflection

Technology and Art

Code

Contact

Dot Product: Algebraic and Geometric Equivalence

The dot product of two vectors is geometrically simple: the product of the magnitudes of these vectors multiplied by the cosine of the angle between them. What is not immediately obvious is the algebraic interpretation of the dot product.

Specifically, this definition:

\[\mathbf{A^TB=\sum_{i=1}^N A_iB_i}\]Why should the sum of the products of the components of two vectors result in the same conclusion?

This article shows two different ways of proving this, one long, and the other one super short (and one I feel is a little more intuitive and less mechanical). In addition, we will conclude with the importance of the dot product in various Machine Learning techniques.

Proof through the Rule of Cosines

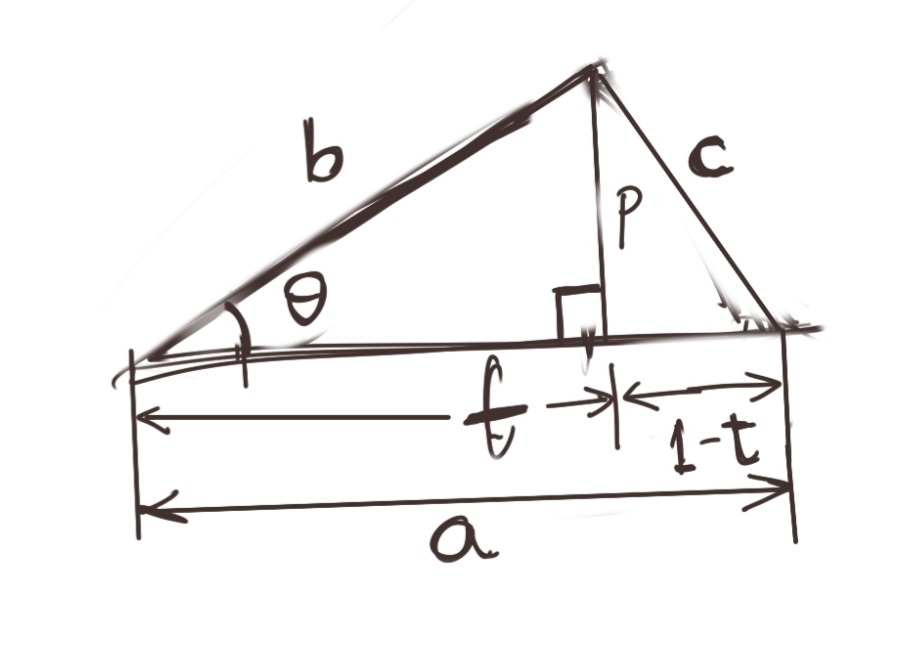

We wish to find the dot product of two vectors, \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\). \(\vec{A}\) has magnitude \(a=\|A\|\), and \(\vec{B}\) has magnitude \(b=\|C\|\). In the diagram, \(\vec{C}\) is the difference of \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\), i.e., \(\vec{A}-\vec{B}\) and has a magnitude \(c=\|C\|\). \(\theta\) is the angle between \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\).

The situation is represented below.

In addition, I’ve drawn the perpendicular \(\vec{P}\) which has magnitude \(p\). \(\vec{P}\) divides \(\vec{A}\) into two parts: \(t\vec{A}\) and \((1-t)\vec{A}\).

Let us list down some basic trigonometric identities evident from the diagram above.

\[{at\over b}=cos\theta \\ \Rightarrow at=b.cos\theta\]We also have:

\[p=b.sin\theta\]By Pythagoras’ Theorem:

\[c^2=p^2+{(1-t)}^2a^2 \\ =b^2sin^2\theta +a^2-2a^2t+a^2t^2 \\ =b^2sin^2\theta +b^2sin^2\theta +a^2-2a^2t \\ =b^2(sin^2\theta +sin^2\theta) +a^2-2a^2t \\ =b^2+a^2-2a^2t \\ \mathbf{c^2=a^2+b^2-2ab.cos\theta} \\\]This is the Rule of Cosines. Note that for \(\theta=90^{\circ}\), this identity reduces to Pythagoras’ Theorem.

Now, from vector algebra, we see that:

\[C=A-B \\ \|C\|=\|A-B\| \\ {\|C\|}^2={\|A-B\|}^2\]Taking the dot product of a vector with itself is essentially its magnitude squared, so we can write, while multiplying everything out:

\[C^TC={(A-B)}^T(A-B) \\ =A^TA+B^TB-A^TB-B^TA \\ =A^TA+B^TB-2A^TB\]Equating the above result with the identity we obtained while proving the Rule of Cosines, we get:

\[A^TA+B^TB-2A^TB=a^2+b^2-2ab.cos\theta\]Since \(A^TA=a^2={\|A\|}^2\) and \(B^TB=b^2={\|B\|}^2\), the above reduces to:

\[-2A^TB=-2{\|A\|}{\|B\|}.cos\theta \\ \Rightarrow \mathbf{A^TB={\|A\|}{\|B\|}.cos\theta}\]The above is the original definition of the dot product, thus we have proved that the geometric and algebraic interpretations of the dot product lead to the same result.

Proof through the Choice of Basis

So, the above proof was somewhat circuitous, going through proving the Rule of Cosines. I’d like to sketch out a shorter, hopefully slightly more intuitive proof, that does not take thses many steps.

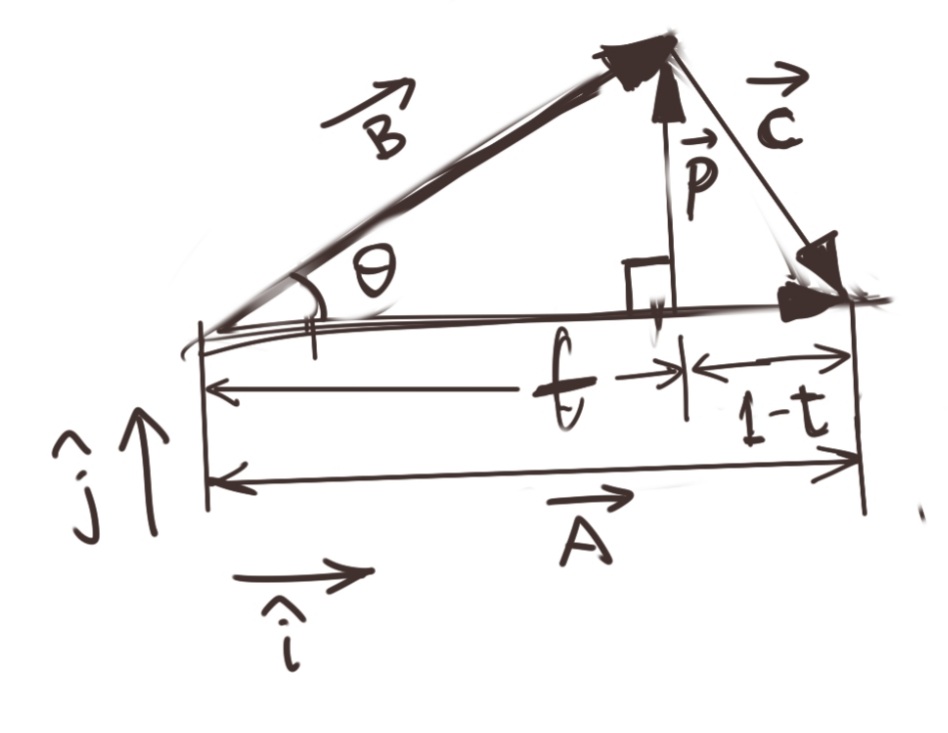

I’ve redrawn the same diagram as above for reference, and emphasised the vector nature of the objects we are dealing with. All other labelling remains the same.

We start with the same identities, namely:

\[at=b.cos\theta \\ p=b.sin\theta\]In fact, for this proof, we will not need the second identity at all, though we will use \(p\) in our work.

Here are the two new things we make explicit. The vectors \(\vec{P}\) and \(\vec{A}\) are at right angles to each other, we will define unit vectors (without loss of generality) \(\hat{i}\) in the direction of \(\vec{A}\), and \(\hat{j}\) in the direction of \(\vec{P}\). That is:

\[\vec{P}=0\hat{i}+ \|P\| \hat{j} \\ \vec{A}=\|A\| \hat{i}+0\hat{j}\]Thus, we can write \(\vec{B}\) as:

\[\vec{B}=t\vec{A}+\vec{P}\]If we take the component-wise product of \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\), which is the same as multiplying \(A^T\) with \(B\), we get:

\[A^TB=t{\|A\|}^2+0.\|P\| \\ A^TB=t{\|A\|}^2 =a^2t=a.at \\ \mathbf{A^TB=ab.cos\theta}\]which is the identity we are seeking to prove.

Applications of the Dot Product

- The dot product is used commonly as a similarity metric between data points. Since it is at its maximum possible value when two vectors are fully aligned. For example, it is used for creating the covariance matrix of a multivariate Gaussian distribution. It is also used as part of different statistical tests for correlation.

- The dot product is an important tool for several proofs where orthogonality of vectors needs to be specified mathematically. Many conditions for results begin with assuming that the dot product of two vectors is zero.

- The dot product usually starts out as a kernel in Machine Learning techniques like Support Vector Machines and Gaussian Processes. This kernel is then set to functions more appropriate for measuring similarity.

- The algebraic interpretation of the dot product is the one most used for computation of the dot product in algorithms.

tags: Machine Learning - Linear Algebra - Dot Product - Theory