Total Internal Reflection

Technology and Art

Code

Contact

Functional and Real Analysis Notes

These are personal study notes, brief or expanded, complete or incomplete. Some concepts here will be alluded to in full-fledged Machine Learning posts.

Convergence

Convergence implies that:

- Given a sequence \(\{x_n\}\)

-

For every \(\epsilon>0\), we can find a \(N\in\mathbb{N}\), such that for \(n>N\), every \(x_n\in X\) differs from a limit \(x_0\in X\) by less than \(\epsilon\). Mathematically:

\[\forall\epsilon>0, \exists n\in\mathbb{N}, \text{ such that } \|x_n-x_0\|<\epsilon\]

Note that this needs to be a metric space. Note that the limit also needs to exist in the metric space. For example, the series \(\{x_n\}={(1+\frac{1}{x})}^n, x\in\mathbb{Q}\) normally computes to \(e\) as \(n\rightarrow\infty\), but since the underlying space is \(\mathbb{Q}\), \(e\) does not exist in this space, and thus this sequence is not convergent.

Convergence for functions can be pointwise or uniform.

Pointwise Convergence

Assume a sequence of functions \(\{f_n\}=f_1, f_2, f_3, ...\) Then \(\{f_n\}\) is pointwise convergent if as \(n\rightarrow 0\), \(f(x)\rightarrow f_0(x)\) for all \(x\in X\) where \(f_0\) is the pointwise limit function of the series.

Note that pointwise convergence allows for values of functions \(f_n(x)\) to jump around for any value of \(n\); as long as the values of \(f_n(x)\) tend to hit \(f_0(x)\) at infinitely large \(n\), the series is pointwise convergent.

Uniform Convergence

Assume a sequence of functions \(\{f_n\}=f_1, f_2, f_3, ...\) Then \(\{f_n\}\) is pointwise convergent if for every \(\epsilon>0,\), we can find a \(N\in\mathbb{N}\), such that for \(n>N\), \(|f(x)-f_0(x)|<\epsilon\) for all \(x\in X\)

\(\forall\epsilon>0, \exists N, \text{ such that for } n>N \|f_n(x)-f_0(x)\|<\epsilon \text{ for all } x\in X\) There is an \(\epsilon\)-tube determined by the sequence number \(N\). All functions \(f_n:n>N\) must have their entire range/codomain lie in this \(\epsilon\)-tube.

Uniform convergence prevents values of a function from jumping outside this \(\epsilon\)-tube. As \(n\) grows larger, the idea is that this \(\epsilon\)-tube will become narrower, and the corresponding \(f_n\) will more closely resemble the limit function \(f_0\).

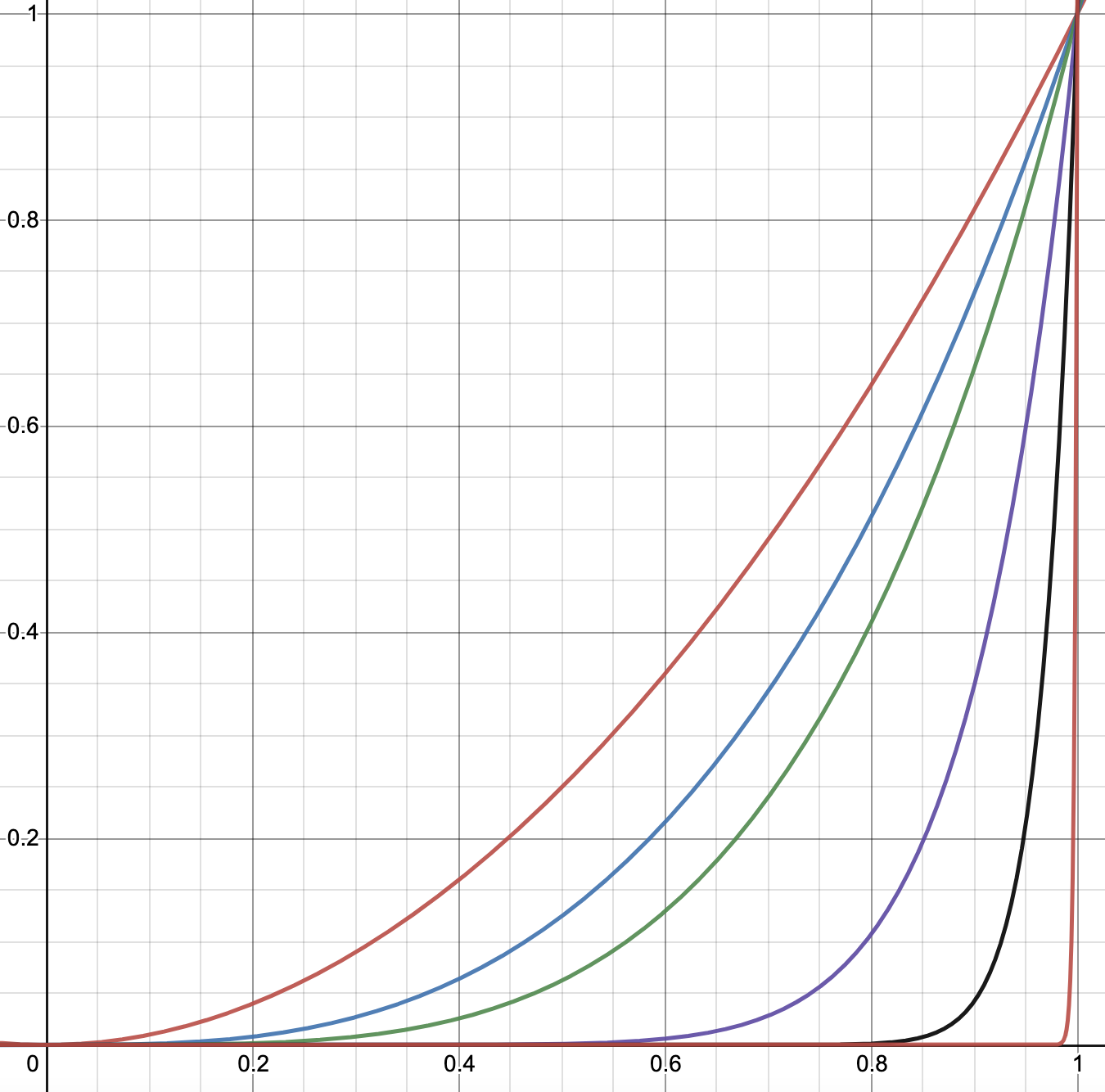

A pointwise-convergent but non-uniformly-convergent sequence of functions \(f(x)=x^n, x\in(0,1)\)

A pointwise-convergent but non-uniformly-convergent sequence of functions \(f(x)=x^n, x\in(0,1)\)

Cauchy Sequences

A sequence \({x_n}\) is said to be Cauchy if the following condition is satisfied:

For any \(\epsilon>0\), we can find a \(N\in\mathbf{N}\) such that for any \(m,n>N\), \(\|x_m-x_n\|<\epsilon\). Note that a Cauchy Sequence is not convergent if its limit does not exist in the field it is defined on.

Again, for functions, they can be Pointwise Cauchy or Uniform Cauchy.

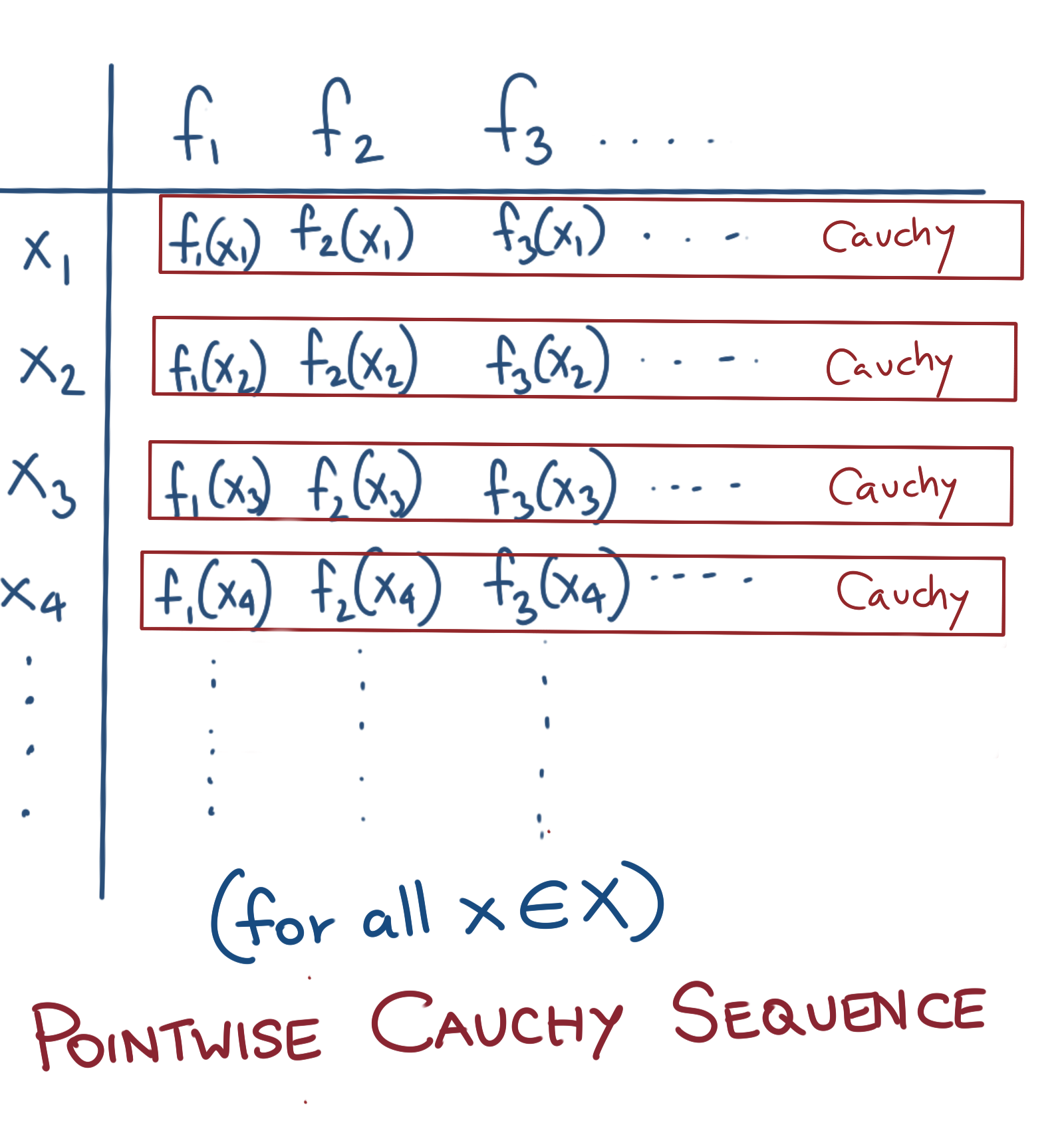

Pointwise Cauchy Sequence of Functions

- Assume a sequence \(\{f_n\}\) defined over a metric space \(X\).

- Fix a \(z\in X\).

- Check if the sequence \(f_1(z), f_1(z), f_3(z), ...\) is Cauchy.

- If the above check is true for every \(z\in X\), then the sequence \(\{f_n\}\) is Pointwise Cauchy.

Diagrammatic representation of a Pointwise Cauchy Sequence

Diagrammatic representation of a Pointwise Cauchy Sequence

Uniform Cauchy Sequence of Functions

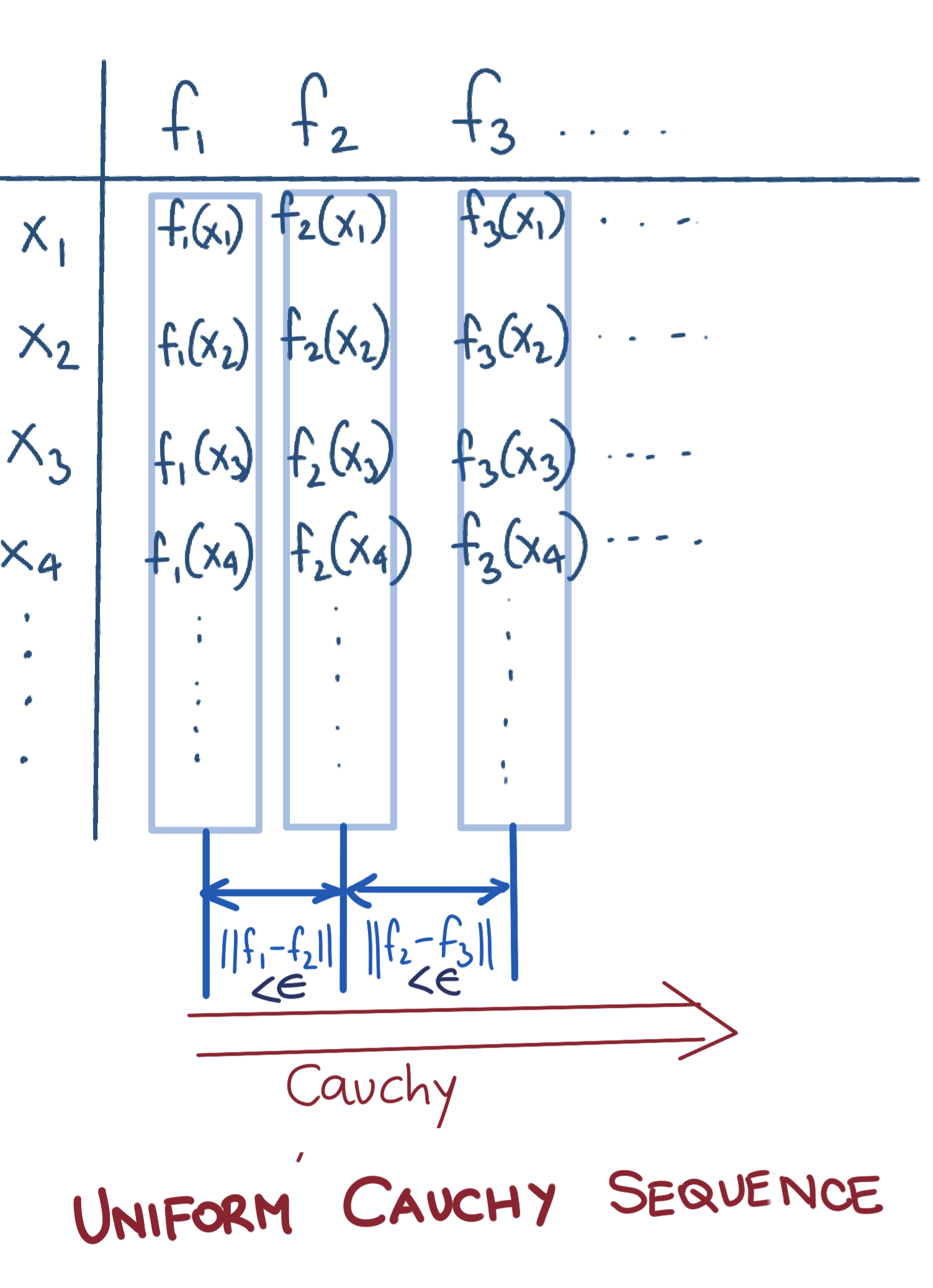

A sequence of functions \({f_n}\) is said to be Cauchy if the following condition is satisfied:

For any \(\epsilon>0\), we can find a \(N\in\mathbf{N}\) such that for any \(m,n>N\), \(\|f_m-f_n\|<\epsilon\). Note that usually the sup norm (\(L^\infty\) norm) is used.

This is what we’d usually mean by a Cauchy Sequence. Uniform Cauchy-ness is a stronger requirement since in Pointwise Cauchy sequences, you have no control how much jumping around will happen beyond any given sequence number in the individual sequences \(f_1(x_0)\), \(f_2(x_0)\), \(f_3(x_0)\), etc.

Diagrammatic representation of a Uniform Cauchy Sequence

Diagrammatic representation of a Uniform Cauchy Sequence

Continuity

Continuous Mappings are mappings that preserve Convergence.

Boundedness of Linear Functionals

Boundedness is defined as follows:

\[\|Tx\|\leq C\|x\| \text{ for } C>0, C\in\mathbb{R}\]Completeness

A space is said to be complete if all Cauchy Sequences in it converge. This could also be restated as saying that the space contains limits of all the Cauchy Sequences it contains.

For example, \(\mathbb{Q}\) is not complete, because quantities like \(e\) do not exist in it, even though there exists a sequence \(\{x_n\}={(1+\frac{1}{x})}^n, x\in\mathbb{Q}\) which gives an arbitrarily close approximation to \(e\), but doesn’t reach the limit as \(n\rightarrow\infty\) because \(e\) does not exist in \(\mathbb{Q}\).

tags: Mathematics - Theory - Notes - Functional Analysis - Pure Mathematics