Total Internal Reflection

Technology and Art

Code

Contact

Two Phase Commit: Indistinguishable Commit Scenario

We review the most interesting failure scenario for the Two Phase Commit (2PC) protocol. There are excellent explanations of 2PC out there, and I won’t bother too much with the basic explanation. The focus of this post is a walkthrough of the indistinguishable state scenario, where neither a global commit, nor a global abort command can be issued.

The Wikipedia entry on the Two-Phase Commit protocol, under Disadvantages, says the following:

Since the coordinator can’t distinguish between all cohorts having already voted to commit and the down cohort having committed (in which case it’s invalid to default to abort) and all cohorts but the down cohort having voted to commit and the down cohort having voted to abort (in which case it’s invalid to default to commit).

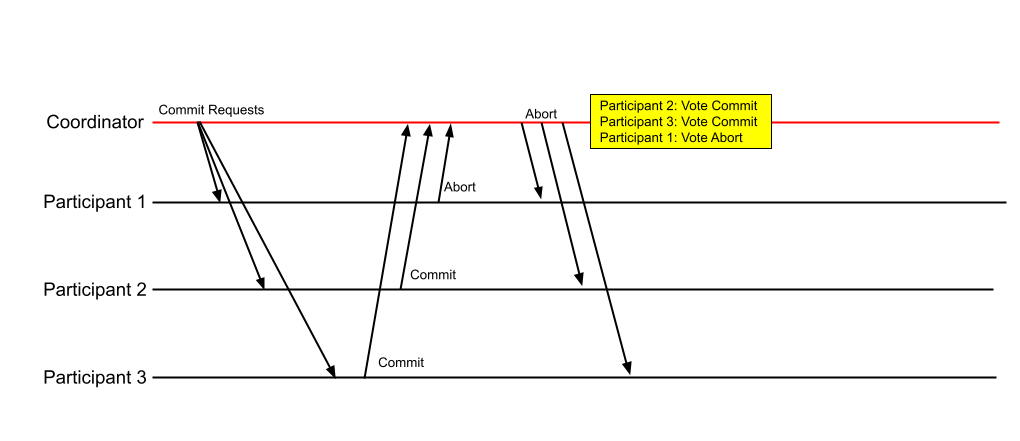

This was somewhat confusing to me at first, but some quick timeline sketches clarified things. We’ll look at the scenarios from the point of view of a participant in the commit protocol. For purposes of this discussion, that participant will be Participant 2. The diagram below shows the fault-free operation of a 2PC-based transaction.

Let us assume that Participant 2 receives the Commit-Request message from the Coordinator, to which it replies with a “Vote Commit” message. If there are no failures at all, all the participants voting to commit would perform the operations in the transaction, including acquiring resource locks and so forth, and would wait for either a Commit or an Abort message from the coordinator. In other words, they’d be blocked.

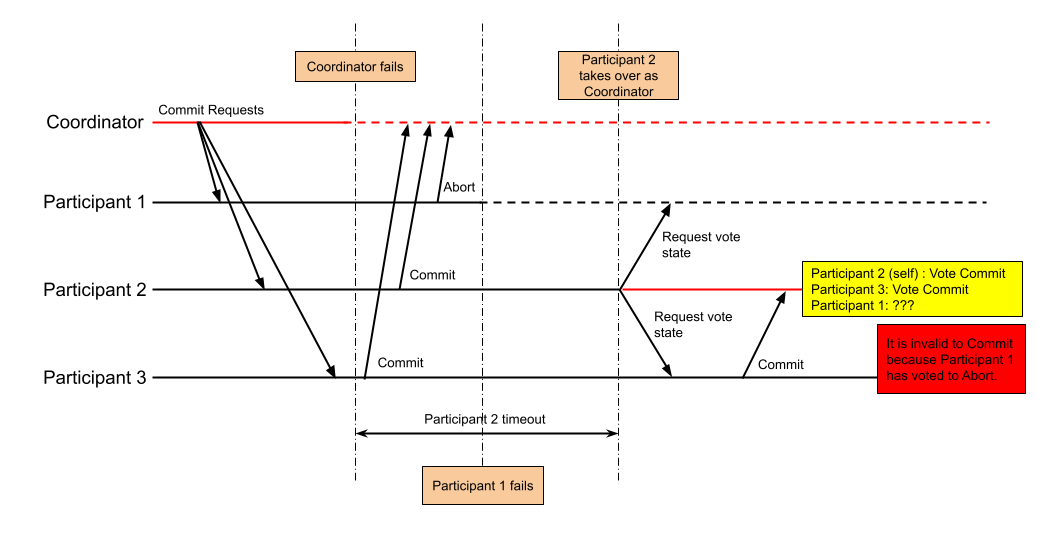

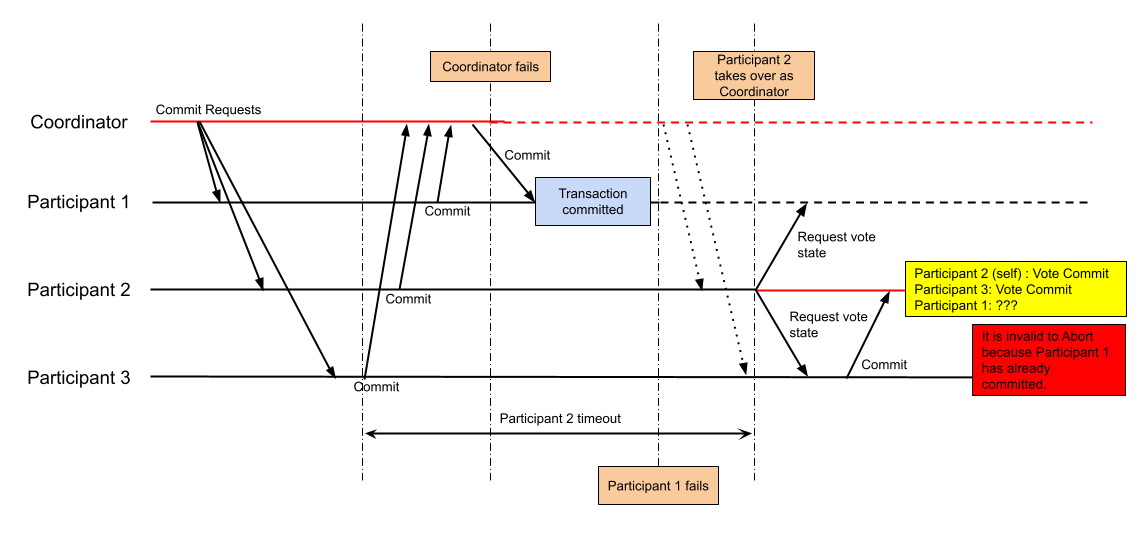

Of course, we do not want to hold up other transactions competing for the same resources indefinitely (which will happen if no Commit/Abort messages arrive at all). Thus the (partial) solution is for one of the participants to take over as the coordinator once a timeout has expired.

So, this is what our scenario is: Participant 2 has sent a “Vote Commit” message, but is blocked waiting for a global Commit/Abort directive from the coordinator, which does not arrive within Participant 2’s timeout period. It is Participant 2 who decides (in some manner) to take over as the coordinator. Let us see what Participant 2 can deduce about the state of the protocol at this point.

It has the following theories about what might have happened.

- The coordinator crashed before receipt of all votes (Participant 2’s vote being one of them).

- The coordinator received all votes, but crashed before it could send the global Commit/Abort directive to all the participants. The implication is that some of the participants may have received the global directive, but Participant 2 is not one of them.

Remember that both 2PC and 3PC depend upon the Fail-Stop model to satisfy the safety property of the protocol. If the coordinator were to recover (or maybe it was just slow), and resume operation, these protocols won’t help. Now, Participant 2 needs to deduce the state of the protocol to complete it. It does this by querying each of the other participants about their knowledge of the protocol (what they voted/whether they received a global Commit/Abort directive). If all the other participants are alive, then the transaction proceeds as usual. Even if some of these participants go down, it is probably possible to deduce what global directive to send. For example:

- If even a single participant had voted for an Abort, then it is safe to say that the transaction is definitely not going to complete.

- If even a single participant had received a global Commit, that implies that the coordinator intended for the transaction to be committed by all participants. The above cases aren’t the ones that are interesting. The edge case is when:

At least one participant has crashed. Assuming this is Participant 1, this means that when Participant 2 asks Participant 1 for its knowledge of the protocol, it receives no reply.

The rest of the live participants have voted to Commit.

Should Participant 2 send a global Commit message, or a global Abort message? The correct answer is: it does not know. Why? Remember the two theories that Participant 2 had about what happened to the coordinator?

Scenario 1: The coordinator crashed before receipt of all votes In this scenario, if Participant 1 had voted to Commit, sending a global Commit might be the right way to go. But if it had voted to Abort, it’d make sense to be pessimistic about it, and just send out a global Abort anyways. This makes sense in this scenario. The situation is depicted below.

Scenario 2: The coordinator received all votes, but crashed before it could send the global Commit/Abort directive to all the participants In this scenario, if Participant 1 had voted to Commit, and if the coordinator had been able to send a global Commit directive to only Participant 1 before the coordinator crashed, then Participant 1 could have committed the transaction before crashing. In this case, it would be a mistake to send out a global Abort directive because, then, effectively, Participant 1 has committed the transaction, while the rest of the participants roll it back. The situation is depicted below.

Thus, the new coordinator simply does not have enough information to unambiguously decide whether to send a global Commit or a global Abort, at this point.

Note: This is a post rescued from my old blog back from 2013. It is instructive to note that technology has changed much since then, but the ideas behind those technologies haven’t.

tags: Distributed Systems - Software Engineering