Total Internal Reflection

Technology and Art

Code

Contact

Resilient Knowledge Bases : Fundamentals, not Buzzwords

We start this tirade with a memorable quote from Alice Through the Looking-Glass:

“Well, in our country,” said Alice, still panting a little, you’d generally get to somewhere else — if you ran very fast for a long time, as we’ve been doing.”

“A slow sort of country!” said the Queen. “Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.

If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!” - Lewis Carroll, Alice Through the Looking-Glass

Durable Foundations in a Shifting Technology Landscape

By the time, I finish writing this, probably half of the technologies I work with daily, will have been superseded by a new set of challengers. You’d be forgiven for thinking that the race to stay relevant is specifically dictated by the (often breakneck) speed at which you can assimilate the latest framework, or the latest “enterprise innovation”.

More importantly, if you are a senior technologist, you are expected to have fluent opinions about the latest and greatest “in-thing”; and that’s fine, since that becomes increasingly a major part of how you add value to clients. It might end up seeming like a race to merely maintain the position you are in.

This is obviously encouraged – at times even mandated – by the sometimes-stringent requirements of knowledge in a particular technology or framework. Must know Kafka. Must know Data Engineering. Our way or the highway. It also encourages specialisation: I’m only comfortable doing .NET projects, so that’s the only kind of work I’d like to pick up.

Sure, I am not underestimating specialisation: indeed, specialisation results in efficiency of a sort, but only in that particular context. Take someone hyper-specialised in technology X, and drop them into an area where they will spend mostly working on that self-same technology, and you have created a dependency, a bottleneck, and a recipe for planned obsolescence, because sooner or later, that tech is consigned to the dust of technology history. There are hyper-specialisations which are fruitful and absolutely necessary, because the work in those areas have much larger ramifications for technology as a whole, or they serve critical functions in society; pure mathematics, for example: we’d be nowhere as advanced without it (and by extension, translating its results via engineering disciplines), or medical science: I’d rather hope that a neurosurgeon operating on my brain has studied specifically about the brain extensively (with the accompanying practice).

But software technology (at least at the commercial applications level) is not that. Sure, you’d need good specialised knowledge if you are designing or programming an embedded system, or if you are writing code to send humans into space. But nooo…we are building a hyper-customisable self-service decentralised platform for accelerating analytics capabilities across the enterprise to provide unparalleled insights into the end-to-end value chain of the organisation. LOL.

Now, to be certain, I am not knocking the intent behind the buzzwords which have been strung together to create the description above. Buzzwords take on a life of their own, and become a useful shorthand for conveying a lot of information without too much description. They serve as a useful layer of abstraction for all the technology that goes into building a solution.

But the technology behind them is always prone to change or fall out of favour, whether it is a product, or a technique. Hanging your star on the Flavour of the Month or the Flavour of the Next Few Months after which Everyone Scrambles for the Next Shiny Thing is not exactly a sustainable way to prosper in the long term. What I am at pains to point out, is that the future is always ready to eat your hyper-specialty for breakfast. What was amazing technology at the time I began working in 2004, is now commonplace, unremarkable.

Resilient Knowledge Base

There is no escaping learning new technology. However, I hypothesise that there are certain steps we can take that will contribute to the longevity of our knowledge base without it being buffeted every so often by the winds of change. And that, in my opinion, is a firm focus on fundamentals.

This is not a new concept, but it is an often deprioritised one. What do I mean by “fundamentals”? Nothing mysterious, just more or less what it says on the tin.

fun·da·men·tal /ˌfʌndəˈmentl/ serving as a basis supporting existence or determining essential structure or function - Merriam-Webster

The idea is that the fundamentals constitute a concept (or concepts) which underlie an observation or a practice or another group of concepts. Usually, the fundamentals end up being a sort of a unifying layer underlying multiple (potentially disparate) ideas.

In the spirit of defining new buzzwords, I’d like to propose this term that I like to use: Resilient Knowledge Bases.

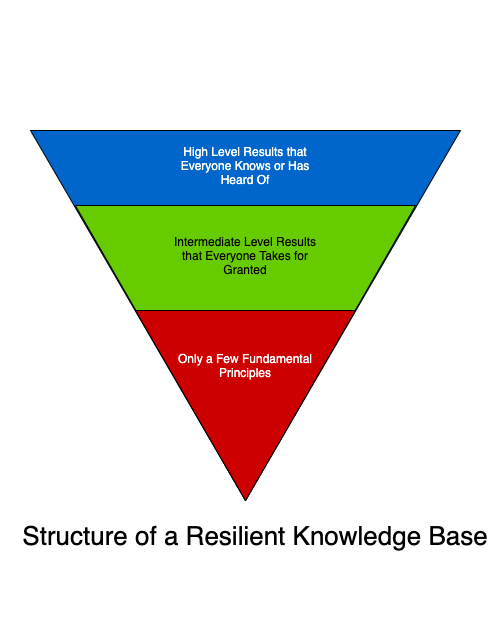

The structure of a Resilient Knowledge Base might or might not be intuitive, but it is certainly simple. Think of concepts building upon more primitive concepts, using logical reasoning as glue between these stacks. Usually though, the concepts aren’t numerous, and the reasoning can sometimes be loose if lesser rigour suffices; as in mathematics, you start with only a few fundamental concepts, and then derive multiple results from those, and then even more on top of those, like an inverted pyramid. The implicit advantage in understanding the fundamentals is then also that you don’t have a lot to “memorise”; most of what you see at the upper levels of abstraction are built atop the sparser layers below.

Examples

Let’s take a look at some examples of what I consider as ‘fundamental’. Your corresponding definitions and levels for what constitutes “fundamental” for these examples may differ, and that’s quite alright; we’ll address that in a moment.

Here’s the lens applied to only a single aspect of the design of a transactional system, maybe a payments integrator.

A few notes before introducing the main lesson. We need to work with the actual system of record (possibly the payment service provider), and thus need to ensure consistency of data between the our system and the service provider. There is not a single way of ensuring consistency, and we would want to make tradeoffs depending upon the operational constraints that are present to us.

But given knowledge of those consistency models, we are in a position to precisely state how the system will behave under unexpected conditions. Thus, we are able to enumerate failure scenarios and edge cases in a much more principled and disciplined fashion.

Taking it a step further leads us to a somewhat more formal (read mathematical) treatment of the properties of such a system. In a distributed system, those are usually Safety and Liveness. The next logical step would be an investigation of the techniques which can assure the existence of certain desirable properties (or the absence of undesirable ones). Model Checking is one such technique.

Of course, this is highly simplified, and the system design of such a component would cover a raft of other considerations. However, the point I’d like to make is this: understanding the technical tradeoffs in this system, adds tools in your kit for designing and reasoning about other types of systems, which are not necessarily related to payments. The snapshot I’ve shown above could form a small facet of this Resilient Knowledge Base, that you can grow and refine over time.

Let’s look at another, more detailed map, this time of a certain technique in Machine Learning, called Gaussian Processes.

The exact details of the graph are not very important; what is salient to note is that the nodes closer to the sources are progressively more generally applicable to a problem statement in the domain. As simple examples, understanding kernels, and by extension Mercer’s Theorem and/or Reproducing Hilbert Kernel Spaces, equips us equally well to understand how coefficients are computed in a different ML technique called Support Vector Machines. As another, more trivial, example, understanding the concept of a covariance matrix and general matrix theory, equips us very well to understand the tools used in a lot of other ML techniques, ranging from Linear Regression to Principal Components Analysis.

Now, everyone will have a different concept of what “fundamental” is, for a different domain, and this is going to be subjective. For example, you can always go deeper than matrix theory and delve into Linear Algebra (and hence to Real Analysis, Abstract Algebra, etc.), or you might choose to stay in the realm of matrix algebra and be satisfied with its results. That is perfectly fine: everyone has their own comfort level, and it would be unreasonable to ask your vanilla developer to start studying Real Analysis just so they can use TensorFlow.

But the point is this: regardless of which level of fundamental detail you are comfortable with, your Resilient Knowledge Bases is determinedly more adaptable to change than the latest version of your favourite machine learning library and its APIs, or the latest buzzword that you may have been asked to get behind. Five years ago, it was Data Lake, now people speak of Data Mesh; several years later, there will be a new term for a new something. For sure, you will need to learn that specialised knowledge to some degree to be functional, but the foundations will always equip you well to work in a different environment, e.g., explaining the fundamentals to a curious client, improving existing implementations, making informed technology decisions based on your knowledge of the fundamentals, or even rolling your own implementations, if it comes to that.

At its heart, you start to think more critically; you do not see technology as a writhing mass of disparate elements that you are forever racing to catch up to, but more of different aspects of a few underlying principles.

I thoroughly and strenuously object to the “Lost without APIs” attitude, which is fine when you have implementations to use in some prescribed fashion, within a limited context. But you do end up doing a disservice to yourself by stunting your growth as a technologist, if this is the stage at which you continue to work in.

Some Suggestions

Far be it from me to claim any authority on how we can get from here to there: I can only offer a few suggestions based on what has worked for me.

1. Seek new ways of thinking about the same thing

Thinking about new ways of dealing with the same problem, can open up many profitable tools at your disposal. As a more mathematical example, take kernels again, like we talked about for Gaussian Processes. Kernels can be understood either through Reproducing Hilbert Kernel Spaces, or through Mercer’s Theorem, which is a statement about eigendecomposition in Functional Analysis. RKHS’s are arguably easier to reason about. Mercer’s Theorem is straightforward, but the fundamentals of it require a more careful study of Functional Analysis to appreciate the results.

In the same way, during system design, thinking of tradeoffs forces one to enumerate various “levers” they have at their disposal. This allows you to develop a range of options instead of resigning yourself to the (sometimes unrealistic) requirements set by business. This sets the stage for a more reasoned discussion in otherwise unreasonable scenarios around what is feasible and what isn’t.

Taking another example from Machine Learning, even something as “simple” as Linear Regression can be dealt with from a probabilistic perspective, in addition to the normal statistical approach. See Linear Regression: Assumptions and Results using the Maximum Likelihood Estimator for a quick flavour. This opens you up to interpreting Machine Learning from more than one angle, and opens up Bayesian Probability as a more broadly applicable tool for deriving results.

2. Read some Theory, and Persevere

Learning on the job is great; it’s usually where a lot of learning usually happens. Unfortunately, in my experience, fundamentals don’t usually present themselves transparently when attempting to solve a problem or write some code or explaining something to stakeholders. Most of that usually can be gained by reading. Here, “reading” is a catch-all term for watching video lectures and discussions with more knowledgeable experts. A lot of theory is not immediately applicable to the situation at hand; instead when you first begin to build your foundations, you will see there’s quite some distance between the result you want to derive (or understand) and where the first building blocks.

As another example in Distributed Systems, the FLP Impossibility requires you to understand the system model as well as a working grasp of different types of logical reasoning (proof by contradiction, for example) to understand the proof.

When you begin, there will be many hurdles. To take a personal example, I struggled greatly (and still do) while progressing through graduate Functional Analysis, because I’d never taken a formal Real Analysis course in Engineering. However intractable the material though, in time, be confident that it will yield to study, and possibly some careful backtracking (which is what I did, teaching myself most of the Real Analysis material I need to progress through my primary texts).

3. Don’t Mind the Gap

Going back to the fundamentals can be an uneasy experience: suddenly many facts (some disparate, some not) that you took for granted, are either called into question, and need to be proved (as in the case of mathematics), or are shown to be working in your case only because the constraints are relaxed in your situation (for example, you’ve never heard of user complain of data consistency issues in your system because the leader database has never gone down, which could have caused possible desync issues with the replicas).

In parallel, there will be many concepts that will seem too abstruse or impenetrable on first reading, and you will be justified in feeling that there are gaps in your understanding. Indeed, in my experience, this feeling of “incompleteness” never goes away. You merely continue to fill the holes in your learning progressively with every new pass of the material. My advice is to not worry too much about getting stuck at the proof / derivation / explanation of a fact / theorem. Give it a fair shot, then move on for the moment, accepting the veracity of said fact. You can always give it several more goes, but that shouldn’t stop you from progressing.

TL;DR

- Do not be satisfied with the minimum needed to get work done.

- Technology and buzzwords changes; adapt to it, but strengthen your foundations progressively.

- Go a few knowledge levels deeper than what your current technology competency requires.

- Persevere while building your Resilient Knowledge Base.

- Accept that there will be gaps in your understanding: know that you can always come back and patch them up.

To end this essay, I think I should let Robert Heinlein have the last word.

“A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly.

Specialization is for insects.” - Robert Anson Heinlein

tags: Technology - Resilient Knowledge Base